“What I had not counted on was discovering how closely a man could come to dying and still not die, or want to die. That, too, was mine; and it also is to the good. For that experience resolved proportions and relationships for me as nothing else could have done; and it is surprising, approaching the final enlightenment, how little one really has to know or feel sure about.” ~Richard Byrd in “ALONE”

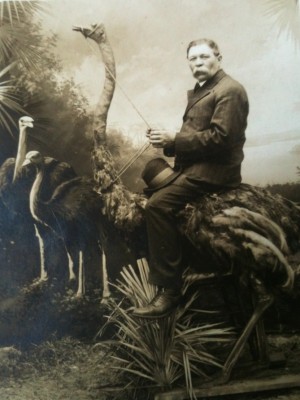

In 1990, my father bought four ostriches — two breeding pairs. We lived on an old dairy farm, and dad and I had retrofitted the barns and pastures, which were perfectly adequate for habitation by placid bovines, to make them suitable for giant, speedy African avians. Ostrich farming was something of a fad in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, and many enterprising farmers had made a small fortune from hide and meat sales. My dad, being the kind of person who suspects the path to success is cleverly hidden, studied ostrich husbandry with zeal, and eventually arranged to have some delivered to our Minnesota farmstead.

The four ostriches who lived within view of my second story bedroom window represented a welcome maturation of Dad’s financial risk-taking. His previous “investment” misadventure had been as a Greeting Cards Entrepreneur, and boxes of them still occupied a large portion of our homeschool learning space. In theory, my father was supposed to work out deals with gas stations, truck stops, and gift stores for the display and sales of these off-brand greetings, but they never sold very well, because they were awful. These cards were printed on high-gloss stock, and were written with all the humor and sensitivity of an excessively sober art school dropout who might list Jim Belushi as a muse. Every color was too vivid, and every hackneyed sentiment was expressed without a shred of subtlety.

The cards embarrassed me. But worse still, since we possessed literally THOUSANDS of them, on special occasions, we never went to the Hallmark store or the main street druggist to purchase, you know, normal people cards. So, on my friends’ birthdays, I’d have to thumb through all these wretched, hamfisted, sickly gleaming wastes of my college fund to find the least humiliating drivel to send them. Sometimes I intentionally moved the boxes of cards right up against the baseboard heaters, hoping maybe they’d catch fire and be disposed of. “That’s awful, Dad,” I imagined myself saying, as if there were ever enough idiots in the entire county to comprise a legitimate market for that tripe.

Yes, the ostriches were better than the greeting cards. Even so, I knew somewhere in the back of my mind that this was another purchase my father had made by flailing in the dark, fueled by a misguided hope of financial bliss. Maybe he wanted his six older brothers to make the drive up from their successful dairy collectives in Iowa, just to see how well-off their kid brother had gotten by chasing his dreams. Maybe that was it. I was only eleven years old, but I knew things probably weren’t going to turn out the way Dad hoped. He worked so hard though, and worked me so hard, I couldn’t help but question my pragmatic doubts. Every fencepost hole I dug and every pound of bird shit I wheeled out of the barn was an investment in my dad and his dreams. The birds — the giant damn birds — meant nothing to me. It was not an adventure, and they were not my pets.

Try as you might, there is no way to establish a connection or rapport with an ostrich. They are very tall — nearly 8 feet — which makes it difficult for them to maintain meaningful eye contact with you. Also, they are quite gawky, and never seem to reconcile with their own bodies, awkwardly heaving the massive bulk of their torso about on spindly, haphazard legs, with their clueless heads bobbing around like an afterthought on their dirty-gym-sock necks. They carry themselves as if continually astounded by their surroundings, and their wide, long-lashed eyes highlight that impression. For an ostrich, life is a very confusing thing, and they don’t seem to be able to make space for relational bonds in their quest to simply survive each hour.

No, an ostrich is not majestic or exotic in the least, not after a week or so of daily interaction anyway. They carry a distinct odor of heavy dander due to the flaky quarter-inch-thick quills of their feathers and their dry skin. They defecate with alarming frequency, and it is as jarring as a sudden accidental birth every time: a half-gallon spew of milky white urine splashes to the ground, followed by dense plum-sized turds. In the winter, the ostriches were often frightened by the steam rising from their own fresh mess, and would flee from it in a state of panic, stupid heads drawn back like some kind of voodoo Muppet, crashing into anything and everything in their inscrutable path.

In such a condition of unbridled fear, the ostrich is a dangerous creature, if not for their 300-pounds, then even more for the claw extending from the larger of their two toes like a sharpened hoof. For this reason, once the birds reached sexual maturity, we kept very respectful distances from them. A being equipped with inadequate intellect, lethal weapons, and frustrated sexuality is a thing to be avoided.

To survive in the African desert, ostriches are well-equipped for environmental extremes, but the desert is a far cry from the bone-chilling cold of Minnesota winters. It can be quite comical to watch the birds frolic in knee-deep snow, with icicles hanging from their eyelashes. To keep them from freezing, each sunset, I would carefully herd them into the barn, pull the twelve-foot high doors shut, and light two propane-fueled patio heaters. The ostriches would settle on the floor, which was covered with eight inches of sand, and watch me turn out the lights with uncomprehending interest.

By the time I was 15, our flock of ostriches had swelled to over 60, with chicks, juveniles, and adult birds scattered about the ten acres of our quaint Victorian-era outpost. Once a year, Dad would rent a horse trailer, and we’d haul a few unsuspecting yearlings off to be slaughtered for their feathers, meat, and hide. Corralling ostriches is a difficult task. They can run forty miles an hour, and are prone to panic. The only way to calm them is to cover their eyes, because ostriches subscribe to the belief that what they can’t see isn’t happening. This is accomplished usually by cornering the bird and covering its head with a snug sack — a technique we called “socking.”

I like to think that I was a talented ostrich farmer. I knew each one on the farm by its markings or habits, and was eventually able to run the entire enterprise with little help from Dad. But one day in January, I noticed a younger male, who was nearly fully grown but without the black feathers of maturity, who did not join the others at the feeding trough. He lurked in the back of the barn and watched the others in their morning feeding frenzy: their beaks scooping mouthfuls from the trough, then jerking their heads backwards like a person swallowing a pill. You could watch the fist-sized wads of food sliding down inside their necks. Six hours later, when it came time for the evening feeding, the lone male still showed no interest in food.

The next day, he did not eat. He didn’t seem sluggish, or visibly ill. He ran in the deep snow with the same stupid gusto he always had. But I was concerned, and separated him from the rest of the flock, in case he had a communicable disease.

I told Dad about the young male and his loss of appetite. Dad, in turn, called one of his ostrich farming mentors for advice. He told me that if the bird didn’t eat, we would have to force feed him. I had force-fed many sickly ostrich chicks before but never a nearly-adult, otherwise healthy bird, and I was not eager to. It was the kind of endeavor that could end in severe injury to farmer, livestock, or both.

After four days without food, the young ostrich began to take more frequent rests and did not venture as often out of the barn. He even spurned water. Dad decided the time had come to attempt an intervention. It happened to be the coldest day of the year, -30 F, and the wind was blowing hard. Dad and I drove to Waconia for supplies. At Hank’s Hardware, we bought eight feet of clear plastic tubing, one inch diameter, and a pipe fastener; at Mackenthun’s grocery, a funnel, six cans of vanilla Ensure Adult Nutrition Beverage, and six quarts of Lemon-Lime Gatorade. Then, we got back in our 1985 F-150, which we left running in the parking lot with the heat on maximum blast, and drove back home.

I brought the Ensure Adult Nutrition Beverage and Lemon-Lime Gatorade to the kitchen, and followed Dad’s recipe: Two cans of Ensure, and one-and-a-half bottles of Gatorade, mixed in a sealable gallon container. At his workbench in the barn, Dad affixed the funnel to the tubing. I carried the liquid mix out to the barn at a full run. We needed to act quickly, before the life-saving nutrient beverage froze. The ailing ostrich lay in the corner of his solitary corral, and watched us enter without rising. Dad reached out to hand me the jug of Gator-sure, and proposed a plan:

“Alright. Let’s hope he stays down. You get on top of him – straddle him. I’ll force his beak open and shove about 36 inches of this tube down his throat. I’ll do my best to hold his head still. Then, you grab the funnel and start pouring the mix down, ok? It’ll be all I can do to keep his head steady.”

I adjusted the scarf around my face, because the condensation from my breath had frozen solid in the wool. “Ok,” I said. “Let’s get it over with.”

The ostrich was too weary to move, and did not seem terribly perturbed when I put the weight of my body on him. I put my hands around his neck. But when Dad began to pry at his beak, the poor creature suddenly came to life. He tried to stand, and I leaned forward, jamming my elbows down hard against his rib cage, a motion which required me to let go of his neck. “Keep him down!” Dad shouted. His scarf had come loose, exposing his face to the cold. His grip on the bird’s head was vice-like, and his jaw set with desperate determination. Unfortunately for both of us, my 140 pound frame was not sufficient to keep an angry ostrich down. I jumped to one side, and tackled him, throwing my arms around his long neck. He lurched violently against the sheet metal of the barn wall. Again, Dad tried and failed to insert the tube. The nutrient mix was already beginning to freeze. We gave up.

My heart was pumping behind my eardrums, and my face was braced against the subzero temperature in a squinting grimace. I couldn’t feel my hands, and there was saliva frozen to my chin. Dad turned away from me without speaking. He began devising a new plan.

He sent me up to the house to fetch a space heater to keep the Gatorade mixture warm. When I returned, he was standing on a step-ladder in the corral. “We’re not gonna try to keep him down anymore,” he explained. “We’re just gonna get him in a corner, then I’ll climb up here to tube him.”

This new plan was employed with success, but it was still a pretty dicey situation resembling a weird rodeo act. From his perch on the rickety old ladder, my father tried to keep the bird’s head still while I pressed from behind to keep him in the corner. The mix sloshed in the jug as I clung to it, and I could hear ice crystals brushing its plastic sides. Dad grunted, “Got it!” and signalled for me to pass him the jug. It was a tricky hand-off, and I took a blow from the ostrich’s knee but held my ground, digging my cheap Sorrell knock-off boots into the sand for footing. With remarkable balance and focus, Dad poured the gallon into the funnel. The bird made a sick gurgling sound and continued his flailing resistance, but we were relentless. Dad threw the empty jug to the ground in triumph.

“We’ve saved a life,” I thought. I wanted to get out of the cold. It was miserable, and the stinging in my toes had become unbearable.

Dad began to pull the tubing out, slowly. Half of the length came out, and the bird was still greatly agitated. Another six inches… and then, bloooshhhh — the ostrich tilted his head back and vomited forcefully straight upward. Ensure and Gatorade rained down on us from above as he twirled away and wagged his head side to side in panic. The force-feeding tube sailed across the barn and Dad nearly fell backward off the ladder. I ran, with slimy lemon-scented vomitus dripping from my gloved hands. The ostrich continued spewing the entire gallon of liquid, and it splashed down the barn walls and froze in strange patterns resembling breaking waves.

I climbed over the gate and stood outside the corral with Dad. He stared forward unblinking, seething. “Dammit,” he said, through his teeth. There was ice on his mustache. “God dammit, we have to try again.” So, we repeated the force-feeding procedure, this time leaving the tube in for a bit longer. Our efforts were met with another drenching and demoralizing puke incident. We abandoned our efforts to save the ostrich, and staggered to the warmth of the house.

Only a few hours later, the ostrich was dead of starvation and exhaustion.

A great beast that only hours before had been capable of killing me was now laid low on the sand, neck stretched flat out before his sadly shrugged wings, head lolled to the side. Warm Gatorade bubbled out of his beak in his final breath and left a small iced-over puddle in the sand.

Death was not a new thing to me; it is a daily part of farm life. I knew decay and its all-shrouding odor. Because the eggs of an ostrich are a curiosity coveted by crafting enthusiasts (hot-glue-gun slingers, silk floristry mongers, bric-a-brac fiends), my parents often ordered me to empty the contents of failed ostrich pregnancies. In practice, this meant that I would take an egg that had been lovingly warmed and rotated in a robotic incubator for weeks, with a viable embryo inside, and drill a hole in its shell with an electric Black & Decker. When the internal membrane was punctured, sulfur and methane rushed to my nose — the smell of a dead chick, entombed in the nutrients nature had provided for its nourishment. With vigorous, careful rhythm, I’d shake the fluid out of the egg through the small hole I had just drilled, hearing the corpse of the chick thud and tumble softly inside. Gossamer bones. Then, I’d slip the end of needle-nosed pliers inside the egg, and, bit by bit, pull the sad dead baby ostrich out through the tiny hole. Sulfur, methane, ammonia. Weird blood. Wet feather down.

But this great big animal dead on the sand in my barn was something different, something I had never encountered before.

By then, the sun had set. Somehow it became even colder. If you have experienced air colder than -30 Fahrenheit, you know that it is a physical thing — you become conscious of every organ in your body (the material sense of them, that they are something like skin inside you, that they are woefully vulnerable) and the air feels real in a concrete and unforgiving way. It is your enemy.

Dad knelt beside the dead ostrich and shoved it with his elbow.

“He’s going to freeze solid. We need to get the hide off of him before that happens,” he said, without looking at me. He was quiet, his jaw twitching and the veins at his temples throbbing red. I didn’t know what to do. I pulled at my stupid red stocking cap, the one I’d worn since I was 12. I was suddenly a little afraid. The red stocking cap was stitched with blue snowflakes.

With the angry tantrum-like resignation peculiar to fathers, Dad grabbed a fistful of feathers near the bird’s spine, and pulled them out. “Get a bag, dammit. Get a big garbage bag. We need to get these feathers out while his body is still warm! Hurry!”

Dad still wouldn’t look at me. I ran to the workbench and brought the box of black plastic bags to his side. I opened one with a grand unfurling motion. Dad took it from me roughly, still without looking at me.

“Aren’t you going to help me? Goddammit, if we don’t get these feathers out while the body’s warm, the hide is ruined. We have to fucking hurry,” he said. I’d never seen him spit so much while talking, and I’d only heard him say the “f” word once before. I recoiled like a child, even though I was 15, even though I’d just tackled a fucking ostrich a few hours earlier.

Now, I have a son of my own and he is 13 years old. When he assists me with household chores, he hangs back and never commits to the task — not out of laziness, but out of fright. I can tell he fears that these seemingly simple routines — mowing the lawn, pulling weeds, using an oven — may have an impossible element that can only be dealt with by someone with uncommon skill. Everything about self-sufficiency is complex and mysterious to him. I know this because the same halting reach of the arms, and the same gape-mouthed subservient expression, and the same sleepwalking slowness came from me, in that moment, with my father in the barn.

He looked at me, finally, and his eyes were cold and blank. I wasn’t his son anymore. We were two nearly hypothermic men shivering in a barn with an ostrich corpse, and that is all.

We pulled feathers with mad haste. Every last feather came out of that damn bird’s hide while he was still warm. And my god, I never said a word. I was scared shitless, because my father was scared. Any harm that could befall me in that barn that night, I knew, would be collateral damage in a fearful and uncertain hurricane swirling inside him. We were on our own, separate but together in the dark solid cold with a dead African bird.

The matter of removing the hide from the corpse was decidedly more complex than defeathering it. The only knives we had were kitchen knives or box-cutters, and we had no rack from which to suspend the carcass for proper dressing. We improvised, and the scant, quavering orange lights in the barn cast shadows that made all the madcap insufficiencies seem macabre.

We tied ropes to the ostrich’s ankles, and hoisted it from the rafters until his beak scraped the floor in pendulous arcs. More Gatorade and Ensure seeped from his mouth. I don’t remember his eyes. We took turns then: One of us would cut at the hide and peel it from the carcass while the other warmed his hands by the space heater — because it is a bad thing to be handling a knife near an expensive hide when one has lost all sensation in his fingers. It was laborious to scrape so carefully with the cursed little box cutter blades at such a surprisingly thick skin, feeling the corpse becoming progressively less warm with every minute. If the flesh froze, the hide would be ruined.

We peeled back the skin from the ostrich’s torso quickly, if not skillfully, and I hope to never do such a thing again. But to remove the hide in one singular, market-ready piece, we needed to get to the smooth flesh of the bird’s thigh. With his head on the ground, followed by nearly four feet of neck and three feet of torso, the thighs and knees were suspended well above our heads. So, to remove the entire hide, we would need to lower the bird from its hoisted position by a foot or two.

We untied the anchoring knots and tried to lower the ostrich a bit, but his neck was frozen stiff. His half-flayed corpse pivoted clumsily on his head, four feet of neckmeat refusing to yield.

I think Dad must have known, then, what we would have to do next, but wasn’t willing to articulate it. Or perhaps he didn’t know. Perhaps this setback was insurmountable in his mind, for a minute. I couldn’t tell. I stayed silent while he Full On Lost His Shit. He stabbed the bird’s carcass with the box-cutter knife with one raging blow and sent it swinging. He kicked the space heater, punted it across the barn. I tied off my anchor line and ran to the retrieve the space heater, because I needed it. My hands were dead. I needed it.

When your hands come back to life after they are dead, the sting is pretty tremendous. I slapped my thighs to hurry the return of blood to my fingers. God dammit god dammit goddammit it was cold.

There was still time to remove the hide, still time to make this bird worth the money we had invested in his existence. But there was only one thing to do, and it was, by far, the least pleasant thing I have ever been asked to do.

We needed to behead the ostrich.

I retrieved a circular saw from Dad’s workbench, because he didn’t own a chainsaw and because a handsaw would have been too slow. Dad held the massive bird steady while I cut, first through tiny gray ethereal neck feathers, then through the the respiratory, circulatory, and digestive vessels. Frozen blood and coagulated tissue spat from the sides of the cruel saw, and I wanted to stop because it seemed so disgusting and senseless. Why did I need to do this?

That thought came and went like the last ebb of a low tide. My moral dilemma was only seconds long, because I was in pain from the cold and because I loved my Dad and because I was horribly afraid of my Dad. When the blade sliced clean through, at last, the ostrich’s neck tipped and fell aside, with an audible “plunk” on the floor like a loosened table leg.

It was 5 o’clock in the morning of the next day before Dad and I were done dressing that bird and cleaning up.

University of Minnesota veterinary students drove to our farm a few hours later to take the carcass in for study. They determined that the bird had died because its intestines were twisted. Nothing could get through the digestive tract, like a kinked garden hose.

We never talked about that ordeal after it happened. Now, my father only faintly recalls that such a thing occurred. We laughed about it once over beers. But maybe he wouldn’t have laughed if he knew that the night I cut off an ostrich’s head with a circular saw, the substance of who I was and what the world seemed to be was rudely reshaped; hunched beside the space heater, I learned that no one was going to make the world safe for me.

*Rahe has lived in Tacoma since 2007 and is active in various community volunteering endeavors. He serves as Editor in Chief of Post Defiance, an online publication covering Tacoma arts and culture.*